Script

:: Blogtober is a blogging challenge whereby bloggers are encouraged to post every day for the month of October. My post topics have been taken from suggestions by friends and family. In general, expect my posts to be shorter, more random and of inconsistent quality! ::

This post was inspired by my far-away friend Amy who suggested that I write about "language and speech".

My brain runs a zillion times faster than my mouth. In the company of more than one person, I sometimes find it impossible to take my turn in the conversation. I see the gaps in conversational flow coming up, but my mouth does not open and the gaps whoosh by. I have something to say. I thought about it while you spoke. I don't feel uncertain about the worth of what I have to say. I don't, necessarily, feel too inhibited or shy to speak. My mouth is just too slow.

I listen to conversations at the school gate, hearing that distinctive pitter-patter as the conversational baton is passed around tight groups of mums. I marvel at the ease with which they observe the universally accepted response time and then chip in with their thought.

I must seem aloof. I've lost count of the conversations I have quietly sidled away from, having entirely failed to find the rhythm of the group. The feeling of standing with others, uncomfortably mute, is a familiar one.

In more formal situations, it is rarely a problem. In a training session, for example, there might be a group discussion and I find I can contribute easily. The social etiquette is different. There is probably someone chairing the conversation. But even if I am not directly asked to contribute, I can. I suspect those interlocutory pauses are longer. The parity of the group is important . People take care to maintain that parity through equitable distribution of opportunities to speak. So, perhaps, people pause a few milliseconds longer before chiming in, to ensure the prior speaker has completed their turn.

It must seem strange to these school gate acquaintances that I do not know very well. Particularly, as one-to-one, I really don't have this problem. I admit that when I am low on meaningful adult interaction, I do occasionally succumb to verbal barfing, "You asked how I am! I am going to TELL you!". Maybe they are confused when having had a perfectly ordinary chat one day, the next (in a larger group) I am no more than a bipedal clamshell. With arms.

I don't need vast amounts of social contact to function and feel good, but it sometimes feels like my head is full of words, buzzing around like angry wasps that can't get out. I think it's probably not an uncommon feeling amongst stay-at-home mums or people who work at home. I think it's why I have enjoyed writing here. I am releasing the words. Go! Fly! Be free! I'm barfing, again.

It may have roots in my deafness. I have had conductive hearing loss in both ears resulting from my cleft palate since forever. The loss is not severe and I get along fine. I have hearing aids, but I don't wear them. They do not offer a great level of correction (although it is possible I haven't persisted long enough to reeducate my brain). They're uncomfortable and clash with my glasses and they're a pain to look after. I know I should wear them. I do rely on speechreading a lot and have become over-reliant on it over the years. It has been suggested that auditory training might help, but I haven't had the time to pursue it.

When there is background noise, hearing clearly is quite difficult. I cannot hear Oscar when we walk on the street, and have to carry him or come down to his level to be able to catch everything he says. In bars and noisy venues, I feel incredibly reliant on speechreading and trying to follow a fast-moving, group conversation is very hard. While I can generally hear the adults at the school gates, perhaps I am just deskilled - my brain is unpractised at processing and responding at the required speeds. Note to self: look into auditory training.

We are a crazy, mixed up family, when it comes to speaking. So here I am, with my own issues. Oscar, on the other hand, is an Olympic-level talker. His vocabulary is ridiculous. I have become used to the look of confusion on adult faces when they see my diminutive, youngest son and hear him speak, "How old is he?". A couple of years ago, Oscar took part in some research at Birkbeck's Babylab, as parts of the BASIS project. At that time he had the vocabulary of an 8 year old. He's still only 5. At nursery this created some social challenges, because he had some difficulties relating to his peers. Happily, this problem has largely fallen away as he has entered primary school. He has that instinctive feel for vocabulary. He is able to infer meaning from context very readily and his memory latches on to new words like a steel trap. I can also report that Oscar has a very well-developed understanding of sarcasm and irony, and already deploys them, complete with huffy teenage sigh. He relishes idiomatic expressions ("Well, that's a recipe for disaster") and can often decode them independently.

At home, I find myself having to frequently and rapidly switch between two wildly different hats, depending on which child I am speaking to. Obviously, Spike's speech and language has developed rather slowly and haphazardly. While his linguistic skills are still emerging, they are not without their pleasures. Of course, his words are like prizes because they were hard-earned, and also because they provide insight into his idiosyncratic experience of the world. This morning, in the car, he exclaimed, "Mummy! Why do the butterflies and moths keep changing the months?!". A simple and weird sentence that requires a lot of unpacking. It is early October and Spike does not like it when the months change. Life can be over-stimulating and challenging for him. The constant mental updating required to keep place with an ever-changing world is exhausting for him. Sameness is a place of refuge. So, he is annoyed that it is suddenly October, when he had only just got used to it being September. I've written about Spike's butterfly and moth phobia before, but this association of an unwanted situation or occurrence with the fluttering fiends is typical of the type of connections his brain makes. He is connecting emotions, rather than looking at causality. He is saying, "When things changes, I feel unsettled and anxious". It takes a certain mental dexterity to get the root of what Spike says. He is, when taken at face value, an unreliable narrator of his own experience. But if you take the time to get to know him, it becomes easier to unpack what he is communicating. We then work on shaping that communication, so that the man on the street can more readily understand Spike's wants and needs and thoughts and feelings.

Another characteristic of Spike's speech is a preponderance of delayed echolalia or "scripting", which is the repetition of learned words and phrases some time after they have been heard and committed to memory. This can be meaningful and functional communication and Spike uses it in quite a subtle, nuanced way. Sometimes the phrase, or script contains the essence or feeling of what Spike wants to convey. People who don't know Spike well might miss the relevance of what he has said, or it may seem out of context. More often he uses scripting as a short cut. He will deploy someone else's words because it is quicker and easier than organically assembling his own response or contribution. In these cases, people generally understand him quite well or at least get the gist of what he is saying.

Spike also uses scripting for non-functional purposes, i.e. without communicative intent. He has a visceral relationship with words. Certain arrangements of them make him feel good and he will say them over and over to soothe or amuse himself. In the trade, they call it "stimming" or "self-stimulatory behaviour". Spike's verbal stims are usually train-based and very often a recitation of the stations on some rail route. These are generally idle habits, though. If he's stimming and you get his attention and ask him a question, he will answer it, so we don't usually try and stop his stims. They can also be beneficial, helping him decompress. Occasionally, when he is tired or very over-stimulated they can be a hindrance. There will be a racing, urgent quality to his bedtime stims. They will go on and on, and he will be unable to stop despite being exhausted.

Like the butterfly example, Spike's preoccupations often loom large in his language. When I picked him up from school today, he said, "Mummy, ask me 'Have you seen my hand dryer?'". I obliged and he responded,

"No. Why are you asking me.

I haven’t seen it.

I haven’t seen any hand dryers anywhere.

I would not steal a hand dryer.

Don’t ask me any more questions."

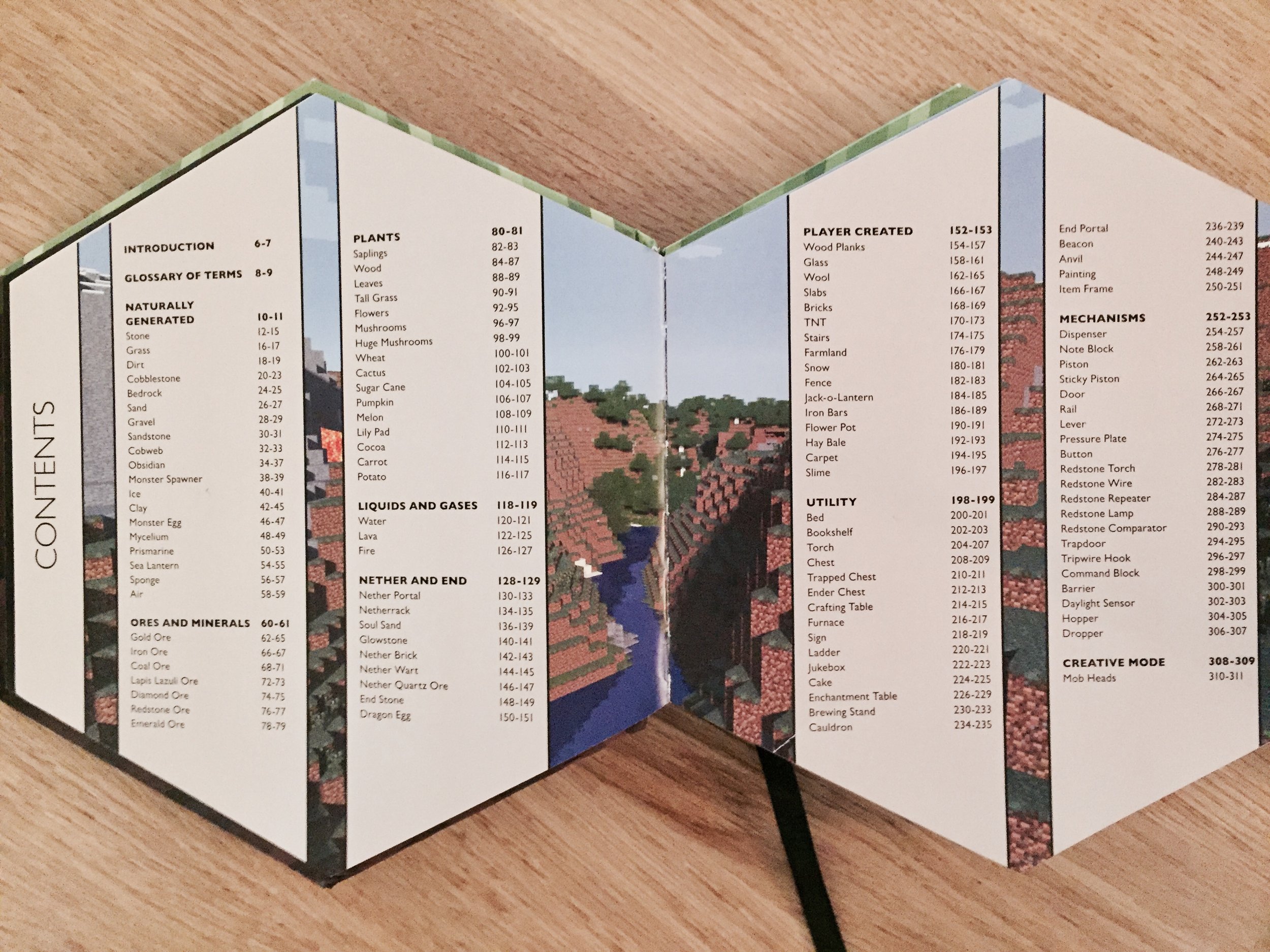

Fans of "I Want My Hat Back" will recognise the exchange. He often plays around with his scripts, bending and tweaking them to better fit his intentions. Spike's hand dryer phobia seems to be rearing its ugly head after a long period of quiescence. Little verbal descriptors of his anxiety are popping up everywhere. Scripting requires a good memory. I'm reasonably certain that Spike's is eidetic. At one point he could recall, in order, the two page Contents of his "Minecraft: Blockopedia" book. He knows the script of his favourite DVD in its entirety, learned from the ever-present subtitles (cf. my deafness). His memory is a huge asset but, like many autistic people, he is having to cognitively, rather than instinctively learn when and how to make use of his store of appropriate responses.

Spike has fun with words, too. Recently, I was conducting my usual post-school interrogation in the car. I asked him whether a particular thing had occurred "today or yesterday". He replied, but I didn't quite catch his response. "Did you say 'Yes, today' or 'yesterday'?", I asked. He was tickled by the similarity of the responses and the confusion they evoked, and chuckled about it for hours afterwards. He has a good sense of the absurd and likes odd juxtapositions of language.

It helps to have a high train threshold when conversing with Spike. I can talk about them all day if I need to, but we're doing a lot of work on his ability to accommodate other people's interests, and to broaden his own. In the meantime, I love my weird, mixed-up chats with him.

For completion, I should mention Ben. He's a good talker. A wordsmith, of course. He secret skill is getting people to do what he wants. Oops. Cat's out of the bag. Although, now I think about it, it's not really a language skill. He is able to use and apply his considerable reasoning abilities to emotional information, and people respond positively to that. Oh, and he can project. I do sometimes have to remind him he is in our living room and not on stage.

Want to read more? When life takes unexpected turns.