Treasure

Not my actual treasure :(

“I stood ankle-deep in the glacial, trickling stream at the forest edge, watching the sunlight scintillate off the riffling flow. My bare toes inveigled their way between the smooth stones and sandy soil of the water bed.

I remained there for long minutes, head bent, scanning the pebbles for the perfect specimen. I had a preference for lozenges of caramel-coloured flint, ideally something which would put me in mind of the fruits of Digory’s Narnian toffee tree.

Instead, my eye was caught by something else. A thrill turned into a shiver as I shifted my cold-stiffened toes and took a careful step forward. Now I could reach the unmistakably brassy-yellow crystalline rock, glinting at the stream edge. Gold!”

Of course, my childish excitement tapered off somewhat as the geologically-minded adults of my company informed me that the nugget was actually iron pyrite, or 'Fool's Gold'.

Our desire and enthusiasm for treasure hunts is primitive. With no need to hunt calorie-dense meat, except amongst the chilled cabinets of the supermarket, the urge is triggered by the quest for other high value items. Literature gives breath and life to these otherwise bare compulsions. As a child, I had a wonderful old leather-bound, gold-embossed copy of R.L. Stevenson's "Treasure Island". Even as a juvenile reader, not yet able to tackle Stevenson's prose, I would leaf through the book, run my fingers over the raised bands on the spine, and marvel at the marbled endpapers and fore-edge. It was a treasure in itself. The title of the book was evocative and exciting and I was not disappointed when I finally came to read the pages within.

Before "Treasure Island" I had relished Enid Blyton's "Five on a Treasure Island", "Peter Duck", the third in the "Swallows and Amazons" series by Arthur Ransome and treasure-based plots in other lesser books like Blyton's "Secret Seven" series, or the "Hardy Boys" adventures. The compelling nature of a trail of clues and the promise of riches has long been literary gold.

In this way, my enthusiasm for finding treasure had been primed, but finding that little mineral lump was the closest I came to the real thing.

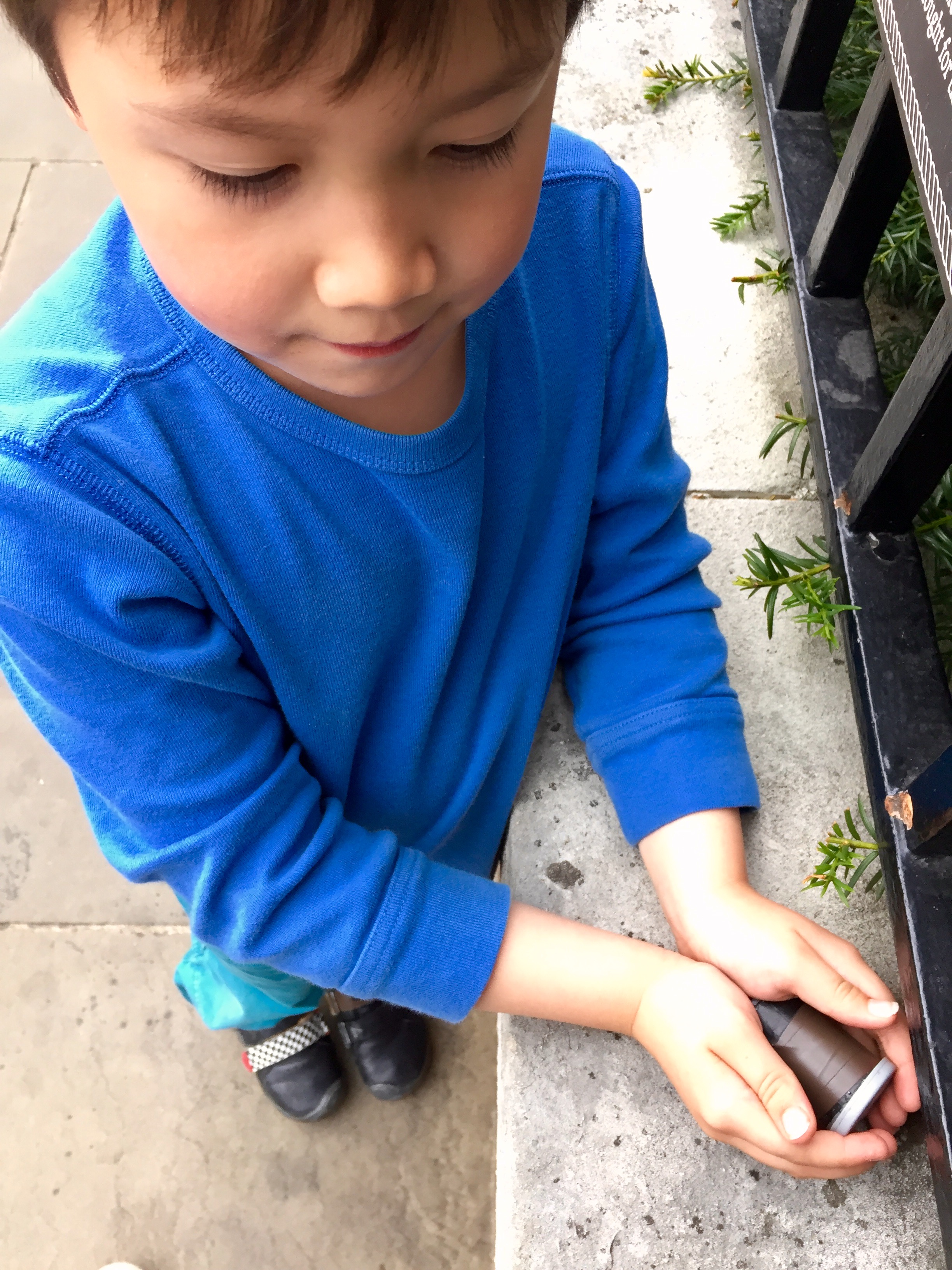

"I FOUND IT!!".

I quickly hushed Oscar and twisted my body to shield his discovery from public view. Behind my rounded back and shoulders, my smallest boy and keenest treasurer hunter squealed almost silently and bounced up and down with glee. When I was sure no one was looking, we inspected the cache, snapped a quick photo* and surreptitiously returned it to its hiding place. Subterfuge in Holland Park.

The first rule of geocaching requires that muggles** do not observe you at play. This global, tech-mediated treasure hunt requires discretion in order that the caches, secreted everywhere from busy city corners to remote villages in unstable nations, remain undisturbed by the unknowing.

Geocaching reminded me that as tantalising as treasure is, it is primarily the thrilling chase that we seek. Many caches, particularly urban ones, will only contain a log book to let the cache-owner know of your find. Despite discovery being the only pay-off, Oscar loved the feeling of being in on a tremendous secret and took the exercise very seriously. He circled the cache locations with faux-nonchalance and side-eyed muggles who strayed close to us. I enjoyed the transformative power of the hunt. Holland Park is a regular haunt of ours, but we found ourselves looking very closely at all sorts of previously unnoticed or unexplored landmarks. The six Holland Park caches had us crisscrossing the green space for about an hour and a half, with Oscar (not a keen walker) striding ahead of me, pulled onwards by the swinging orange needle of the Geocaching app compass.

My father recently told me about a wonderful 1970s publishing phenomenon of which I was previously unaware. Kit Williams, an artist/illustrator and author, spent a month fashioning a beautiful jewel-studded, 18ct gold filagree hare - a genuine treasure. Before burying the hare in a ceramic casket in a secret location, he painted 16 pictures containing various riddles and puzzles, and one large puzzle which, when solved, would reveal the whereabouts of the real life treasure. Williams published the paintings in a book entitled "Masquerade" which was aimed at children although, in reality, most of the puzzles were too fiendish for young minds. Looking at painstaking breakdowns of the larger puzzle, the solution is heinously obscure.

Unsurprisingly, given the reward on offer, the book sold in the hundreds of thousands. Children and adults poured over the pages of Williams pastoral and oddly idiosyncratic art, trying to gain traction on the location of the hare. A year on, and the puzzle had not been solved. Public grumbles and allegations of chicanery forced Williams to release a further clue in The Times. This puzzle piece was to bring a couple of tenacious treasure hunters within feet of the hare. Despite their feats of mental agility, they were pipped at the post by a dubious character who claimed to have stumbled upon the prize at its location in Ampthill, Bedfordshire.

Investigative work by the editor of a local newspaper revealed that the hare finder was connected to a man whose girlfriend had been William's girlfriend at the time "Masquerade" was created. It was a disappointing end to a long season of questing***. A good story, though!

* Ideally, you should identify yourself on the log book, but we had no writing implement.

** Non-geocachers.

*** I thoroughly recommend this long-read of the whole sorry tale which, improbably takes in Agatha Christie, the wives of Henry VIII, Caron Keating, early home computing and a really awful game called Hareraiser - Part 1, Part 2

Want to read more? Our annual pilgrimage to the Serpentine Gallery pavilion.